Since it’s early stages of my project, I am focussing on brackets in romance in prose, but eventually I’d like to cover brackets in all kinds of romance, prose, poetry, and drama. So, as preparation for that second stage (and because it’s fun), I called up two manuscripts of John Harington’s Orlando Furioso translation. One, a beautifully-bound clean book in secretary hand, both by Harington himself and his scribe (Bodleian, MS Rawl. poet. 125.). One a manuscript by a private person, one Richard Newell who transcribed choice passages of the poem, putting them together with copies of letters and accounts (MS Malone 2).

The book is quite a big folio, and wrapped in smooth but ungainly vellum. A book of use. Around ten to thirteen pages at the front and back are written in mixed secretary-italic hand with a fairly thick nib, and still dark black ink. The letters on the one side, and the accounts on the other, are dated to 1623.

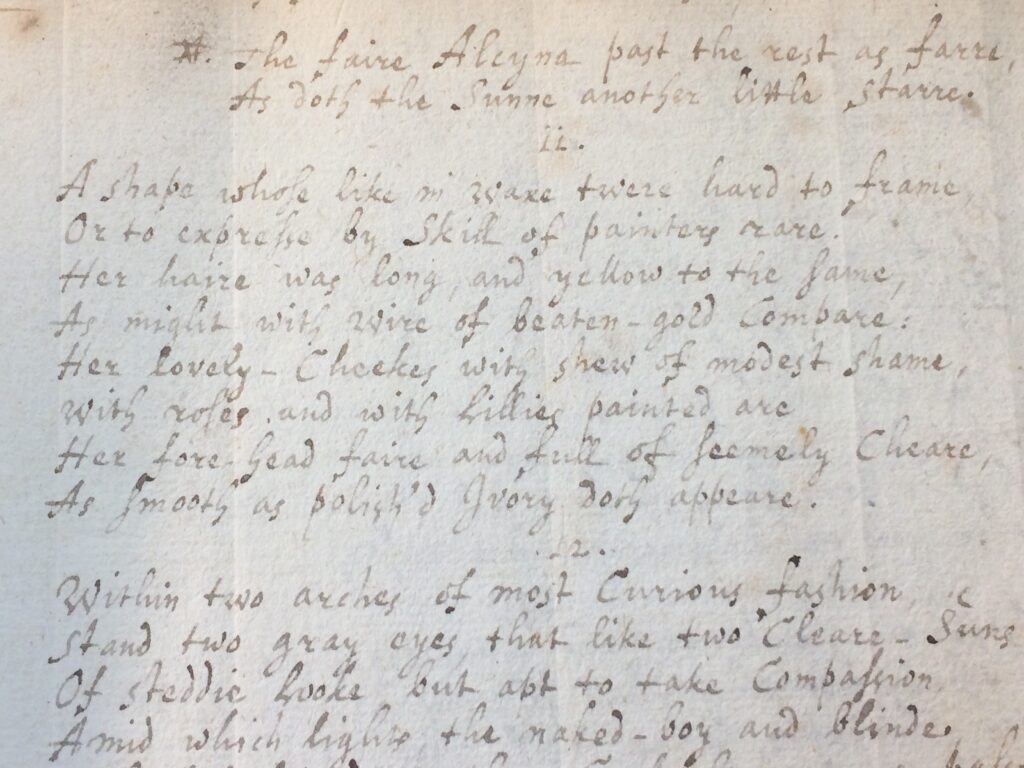

Sandwiched between these letters and accounts, however, the largest part of the manuscript, is a selections of Harington’s 1591 English translation of Ariosto’s 1532 Italian romance Orlando Furioso. At the beginning of the tidy, nearly faultless transcription in a fairly small, neat italic hand is the date, 1645, and even the months that the writer worked on it (January and February). The ink is quite fair, and/or strongly faded, making it hard to read sometimes.

Her lovely-Cheekes with shew of modest shame With roses and with Lillies painted are’.

Why ‘lovely-Cheekes’ and not ‘modest-shame’? Perhaps cheeks can only be lovely, while there are different kinds of shame. Or is this proof Newell’s hyphens are, well, not that deliberate after all?

I’d have to really look through the entire copy in order to assess that with more grounding in numbers of incidents. As it is, though, only because each and every case has not yet been judged, it doesn’t mean it’s not there. Because it is. There. ‘Lovely-Cheekes’.

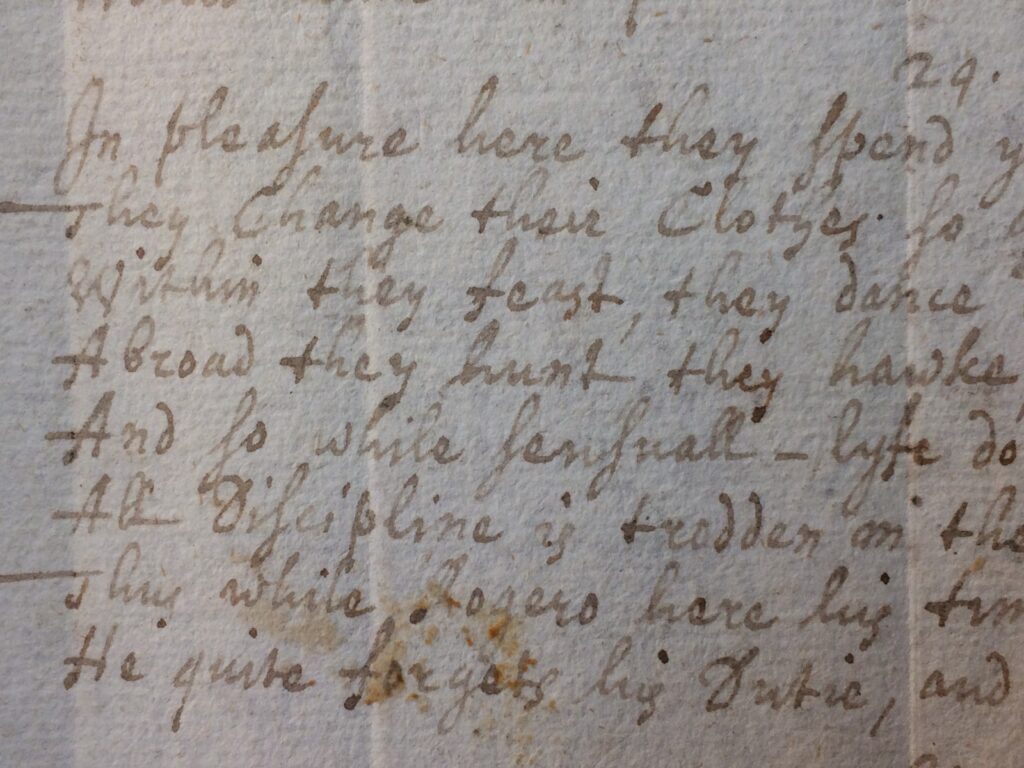

My particular favourite comes in the description of two lovers, sporting a carefree life devoted to such very naughty things as hunting and frequent changing of clothes. And, of course, kissing in a way that makes it impossible to tell which tongue belongs to whom. We call that the French way.

In short: they lead a truly ‘sensuall-lyfe’ (line 5 below).

In short: they lead a truly ‘sensuall-lyfe’ (line 5 below).

Wrapped in each other, tongues twisting in French kiss, the hyphen makes their physical bonding visible. The distinction between adjective modifying noun disappear; the discrete boundaries between bodies do. It’s all one thing, the platonic whole, hyphenated sex. Sensuall-lyfe.

[last updated 31 August 2022]