~ Renaissance ~

The Tudors, that bawdy (totally absurd and weirdly accurate) series about King Henry VIII has brought early Reformation history into a strange kind of public consciousness. But that was not what started my love for those shimmering magical and awful uncertain years between schism and Shakespeare.

My first term at university was all about medieval literature with its knights, and unicorns, and lyrics to the Virgin Mary. I thought my heart was settled on that period, but then I learnt about the Renaissance, and was sold heart and soul. There’s something about their way of thinking and writing (and living!) that’s captured me,and won’t let me go. Not that I’d ever want to.

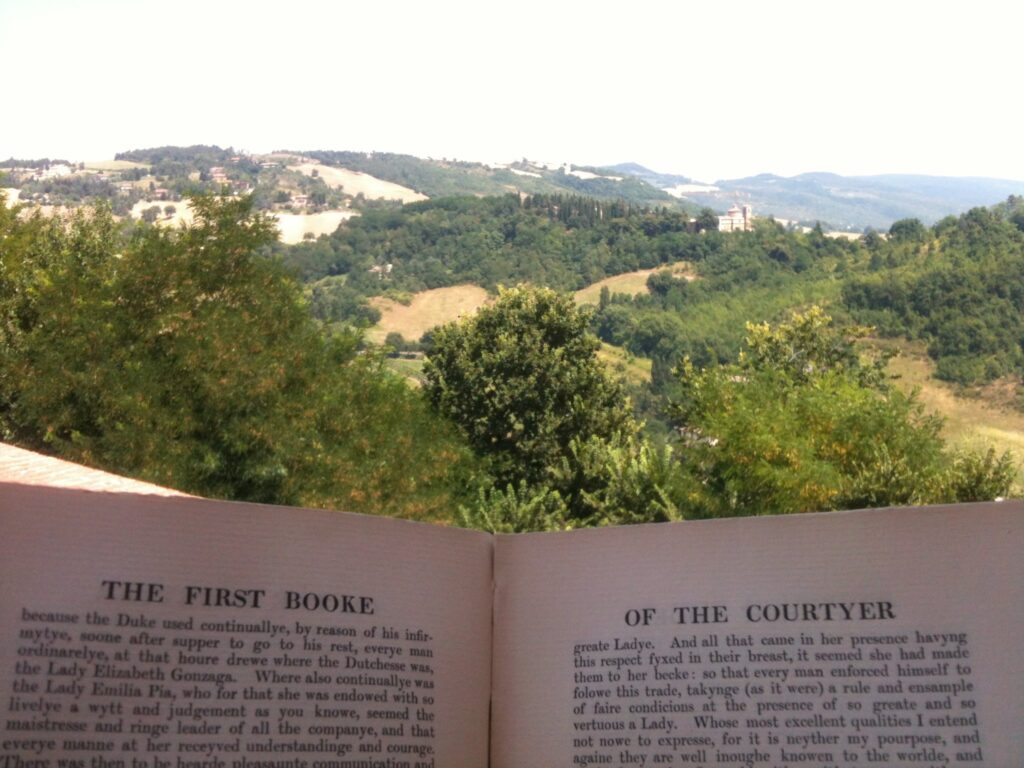

During my undergraduate studies at Cambridge, I followed all courses and all lectures and all seminars on Renaissance literature the university offered. I loved getting stuck in the formal complexities of early modern poems and prose – like castles with a thousand nooks and crannies to discover and explore.

Although I appreciate drama, I enjoyed non-dramatic texts by Edmund Spenser, Philip Sidney, and Thomas Wyatt. I spent many happy weeks tracing Bible translations from old languages into new ones, and losing myself in details of words, and knotty theology, perhaps a bit of a rare pursuit for a young person…

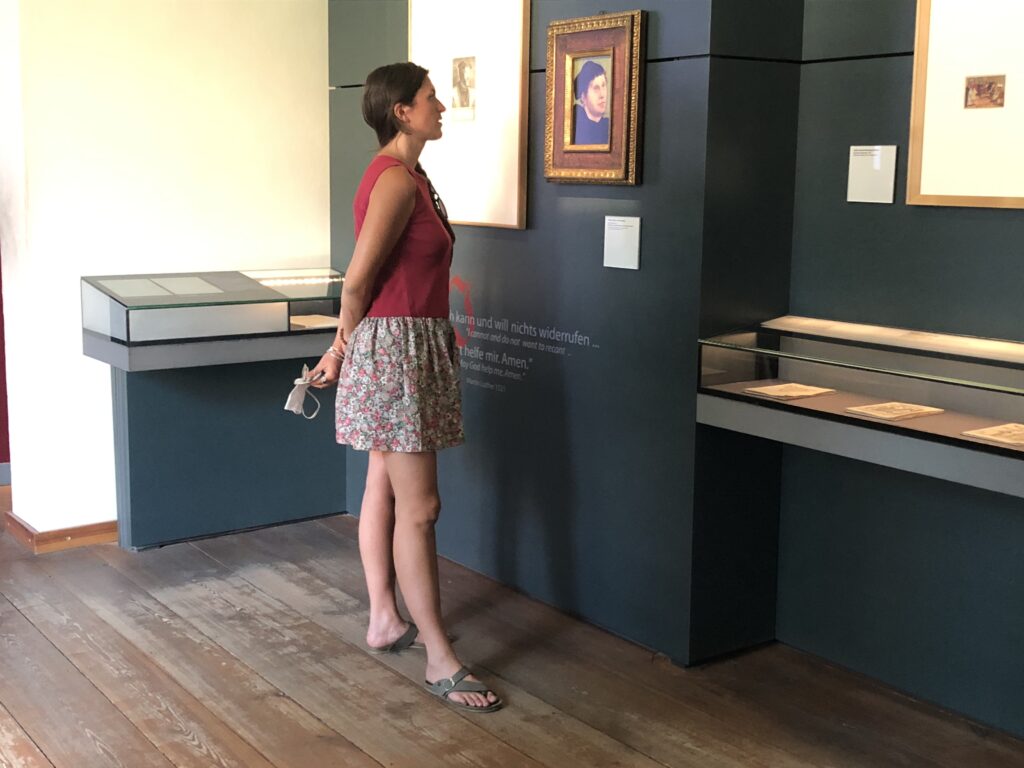

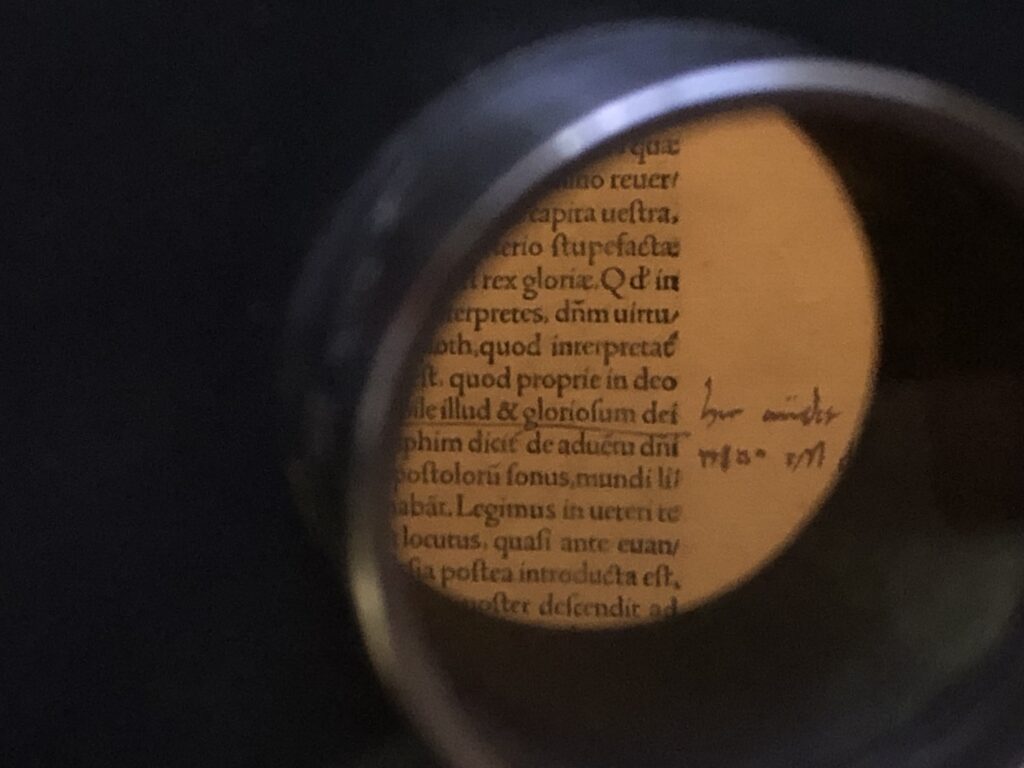

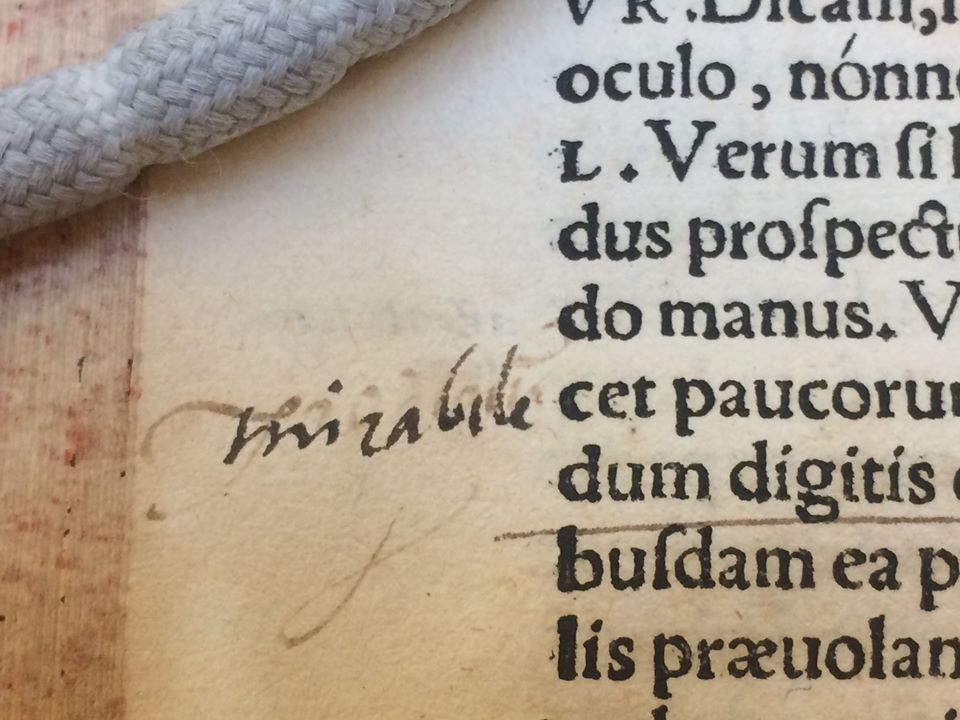

The Master’s at Cambridge gave me the foundations for independent research. And I learnt to read beautiful but indecipherable Renaissance handwriting!

During the Master’s, I also developed the nugget of what would become my PhD thesis: the role of line repetition in remembering poetry, and poetry remembering. Remembering the collective past. Past love. Music from a bygone era. St Andrews in Scotland became my home for three research years on oral traditions, repetition in music and poetry, court culture under Henry VIII, and Shakespeare’s musical drama. While I did not learn how to golf, I did play folk music in the (only) pub of that lovely little (read tiny) town where Kate and William met.

As I was on the last laps of my PhD, I started my first job at the University of Geneva in Switzerland. We were a team of four researchers, working on very early translations of Shakespeare’s plays into German. In the sixteenth century, English travelling companies were touring the continent, and eventually translated plays by Shakespeare and his contemporaries into all sorts of European languages. They also adapted the plays, according to cultural background. Read more about the project and publications here.

After Geneva, my nearly decade-old passion (obsession?) for punctuation called me, and I examined the history and literary uses of punctuation in Renaissance literature. This project found a home at the University of Sheffield where I was Leverhulme early Career Fellow for three years. Only that the pandemic made trawling through the archives, looking for old books and smudgy punctuation marks somewhat impossible!

So, what exactly is it that keeps me hooked?

While I do enjoy the occasional free verse and improvisation, I’m a sucker for form. Perhaps paradoxically, forms free me, whether it be of a poem or a dance (standard dancer here…). Renaissance thinking is all about structure: wearing old structures like new clothes, inventing new structures to fit new conditions, creating super convoluted structures as a mark of elegance and wit. People thought a lot about how to present information in a way that’s most true to the subject — which is not always the “easiest” way! So, wrestling with difficult stuff in sometimes maddeningly constricting literary structures attracts me and keeps me addicted. Always dissolving when I try to grasp and fix. Always that little bit out of reach, making me chase, and chase some more…

Perhaps it’s that obsession with (and love of!) form that had people wonder about how to be with one another. Then again, people always have and always will worry over inter-human connections… I’m fascinated how specific and minute some of the behavioural codes of the Renaissance were, and how that impacted literature, how it showed in texts. Detail matters, every element communicates. In the same way that a look, a seemingly obscure allusion, a position in a room spoke without speaking, so did the arrangement of words on the page; the size of letters; the decorated border; illustrations. I like the refinement of Renaissance culture. And its simultaneous robust sense of humour and rigorous thought discipline. They weren’t shy to think deep and hard about difficult things, brave enough to be led by curiosity which, sometimes, led to uncomfortable places. And then to sit in them.

This is a skill we currently don’t seem to master, or even be interested in. But during the early modern period, generations of boys (and some girls) were trained in versatility of thought: at school, they learnt in utramque partem debating, that means, finding arguments for both sides of a hypothesis, and switching back and forth during the defense. Is it justifiable to kill a tyrant king? Is it good to get married, or not? Perspective changes like that didn’t only just make persuasive lawyers, they also produced a host of minds that knew about, understood, and felt the exquisite complexity of life. I appreciate that.

While we’re at the moment nowhere near as interested in the other side as early modern people were, we do share lots of circumstances with them, which makes the period feel close to our way of living: every human life has always been challenging, but the Renaissance was especially so, witnessing how deep religious chasms split societies and caused hundreds of years of war; explorations into far corners of the world laid the structures of the (post-)colonial world we now live in; the printing press pushed people into the profoundly changed world of fast and identical repetition of text which one may compare to the internet. When reading Renaissance writing or engaging in Renaissance culture, they’re always talking back.

What I most like, I think, is that people just really really loved literature. Yes, sure, educators and humanists like Thomas More apologised for literature as the perfect way to learn elegant Latin plus some virtues coming in handy when advising kings and princes as commonwealth civil servants or lawyers (a straightforward career path for schoolboys and Oxbridge students). Sure we can say so, and focus on the functional aspect of art, teaching good speech and ethics. We still do, by the way. Find justifications.

Beyond the noise about how reading is good for something else, people also just loved it for itself. Just because. Just because the story is exciting. Just because the feelings expressed in a poem strike a chord inside. Because the language is lovely.

For Renaissance people, learning mattered. Literature did. Just because.

No rest for the wicked! Always eager to get my ruff out. Here embodying Pride (together with Anger) at a Seven Deadly Sins party in my first year at uni.